Gene Therapy Vector Choice Affects Carcinogenicity

A new study conducted by the National Institutes of Health found that a certain vector used in gene therapy (and its insertion site in the genome) may be associated with an increased risk of liver cancer.

A new study conducted by the National Institutes of Health found that a certain vector used in gene therapy (and its insertion site in the genome) may be associated with an increased risk of liver cancer.

Through a mouse model of the study of methylmalonic acidemia (MMA), a genetic disorder that prevents the body from metabolizing certain proteins and fats, scientists have discovered that the type of viral vector that is used to infect cells in gene therapy may play a role in future cancer risk.

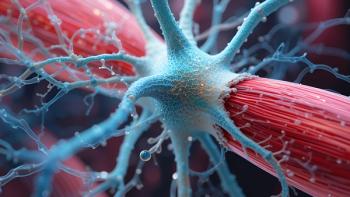

Using adeno-associated virus (AAV) as vector to treat MMA was found to be an effective gene therapy to treat mice bred to develop the condition. Researchers from the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) also found, however, that in long-term follow-up studies, the mice treated with this vector were more prone to developing cancer. The vector’s insertion site triggered elevated expression of nearby genes associated with cancer.

When investigators used an alternate AAV vector to deliver the corrected gene to treat MMA, the vector inserted into another site-one that was not associated with the same carcinogenicity. Similarly, when lower doses of the original AAV vector were administered, the incidence of cancer in the mice dropped compared with a control group.

It is important to note that the microRNA molecules in the mouse genome that were associated with increased cancer risk are not found in the human genome. Despite this fact, therapeutic gene vector choice and vector insertion sites could play a significant role in genotoxicity, the authors of the study concluded. "Most of the AAV integrations that caused liver cancer landed in a gene that is not found in the human genome, which suggests that the cancers we observed after AAV gene therapy may have been a mouse-specific phenomenon," said Randy Chandler, PhD, lead author and NHGRI staff scientist. "However, these studies do convincingly demonstrate that AAV can be a cancer-causing agent, which argues for further studies.”

Source:

Newsletter

Stay at the forefront of biopharmaceutical innovation—subscribe to BioPharm International for expert insights on drug development, manufacturing, compliance, and more.